>> About the books > Hasina > Feedback

What people are saying about Hasina

What people are saying about Hasina

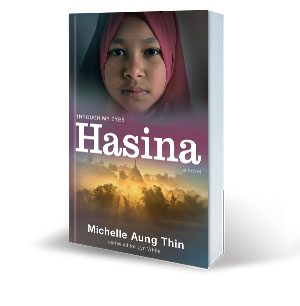

'Hasina tells the story of the persecution of the Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar through the eyes of fourteen-year-old Hasina. It is an engaging, nail-biting novel that offers children both windows into another’s world and mirrors into their own. The phrase ‘windows and mirrors’ was first coined by Doctor Rudine Sims Bishop in 1991, and refers to the need for children to see themselves and others in their stories. Through the character of Hasina, Australian children can see themselves in the familiar experiences they share with her: quieting down younger siblings, solving maths problems at school or having teenage crushes. There is so much about Hasina that is relatable, and through this relatability the story shines a light on all the things that connect us as people, no matter how different our lives are. It is through these differences, however, that children are also offered a window into Hasina’s world. Readers are introduced to a world so unlike the one they know in Australia. One with different languages, foods, clothing, customs and religious practices, and one where persecution forces Rohingya families like Hasina’s out of their homes - and their country.

Much of the novel takes place in the aftermath; with Hasina and her small but vital community of family and friends learning to survive and rebuild as best they can. Through this, the myriad of complications and crimes that arise in times of oppression are explored. The family must navigate sickness and starvation, and Hasina must protect six-year-old Araf from being stolen and sold. The story also tackles issues of women’s rights and gender inequality in an undertone throughout. By placing Hasina as the protagonist, the roles, rights and expectations of women and girls are of constant consideration in the background of the story.

Importantly, the story examines the ongoing impact of trauma in a realistic way. Hasina’s aunt and cousin are refugees who fled their home years prior, and the trauma of that experience is shown through Ghadiya, Hasina’s cousin, who suffers from post-traumatic stress. As Hasina goes through her own trauma in the novel, her inner thoughts and feelings perfectly capture the sense of fear, confusion, pain and emptiness of trauma. However, through small acts of kindness by others (most notably a stallholder in the bazaar and a lawyer from Sittwa), they also capture those of hope, compassion and love.

Hasina is such an important book for Australian children, particularly as our country continues to deny basic human rights to refugees. Beautifully crafted, it shines a light on the realities of persecution and displacement, and shows the strength of perseverance and kindness in the face of bigotry and fear.'

Sarah Mokrzycki, sessional lecturer/tutor and PhD Candidate at Victoria University, VIC